Nearly seventy years after its publication, The Cat in the Hat remains one of the most debated books in children's literature. Is The Cat in the Hat appropriate for children today? The answer depends on what you value in early reading experiences. This 1957 classic delivers controlled vocabulary and engaging rhythm while sneaking in themes of rule-breaking and consequence that some parents find concerning.

Dr. Seuss (Theodor Geisel) wrote this book specifically to address the "Dick and Jane" problem—boring early readers that failed to captivate young minds. Using just 236 unique words, he created a story that feels spontaneous and chaotic while maintaining the repetitive structure beginning readers need. Fans of Green Eggs and Ham or Hop on Pop will recognize the signature Seussian approach, but The Cat in the Hat introduces more complex moral territory.

A Rainy Day Revolution

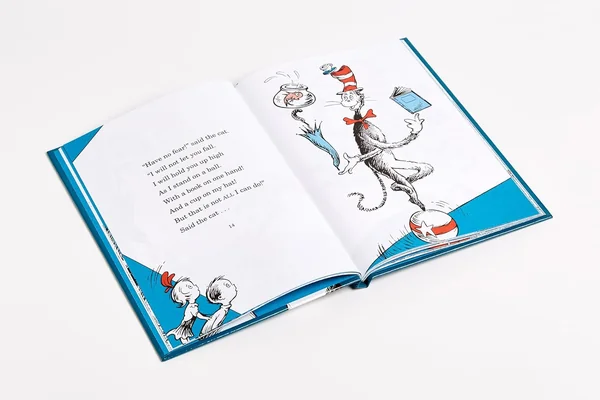

The setup couldn't be simpler: Sally and her brother sit bored on a rainy day while their mother is away. Enter the Cat—a tall, anthropomorphic figure in his iconic red and white striped hat and red bow tie. What follows is controlled chaos as the Cat introduces increasingly elaborate tricks and games, despite protests from the children's pet fish who serves as the voice of caution and rules.

The genius lies in Seuss's restraint. Working within the limitations of a controlled vocabulary, he creates genuine tension between order and disorder, responsibility and fun. The Cat isn't simply entertaining the children—he's challenging the entire concept of following rules when authority figures aren't present.

Rhythm That Teaches Reading

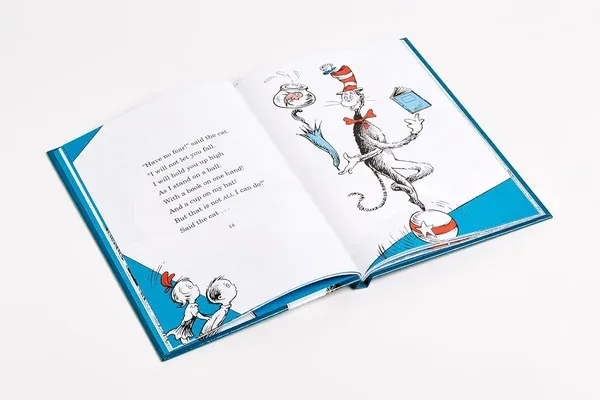

Seuss's mastery of rhythm and repetition shines throughout the book's 61 pages. The anapestic tetrameter (the bouncing rhythm that makes Seuss so memorable) helps beginning readers predict upcoming words and maintain momentum when they encounter challenging vocabulary. The illustrations work in perfect harmony with the text, providing visual context clues that support reading comprehension without overwhelming the page.

The controlled vocabulary doesn't feel artificial because Seuss chose his 236 words strategically. He repeats key words—"cat," "hat," "fun," "game"—enough times that struggling readers gain confidence, while the rhythm carries them through unfamiliar terms. This makes it genuinely accessible for children reading at a first or second-grade level.

The Troublemaker and the Voice of Reason

The Cat himself embodies the appeal of breaking rules. He's charming, confident, and utterly unconcerned with the mess he creates. The fish, meanwhile, represents the internalized voice of authority—constantly warning about mother's return and the consequences of the Cat's games. Sally and her brother occupy the middle ground, torn between temptation and responsibility.

What makes these characters endure is their archetypal nature. Every child recognizes the pull between doing what's fun and doing what's expected. The Cat doesn't represent pure evil—he represents the part of childhood that questions why rules exist in the first place. The fish isn't a killjoy—he's the part of growing up that understands consequences matter.

Chaos, Cleanup, and Moral Questions

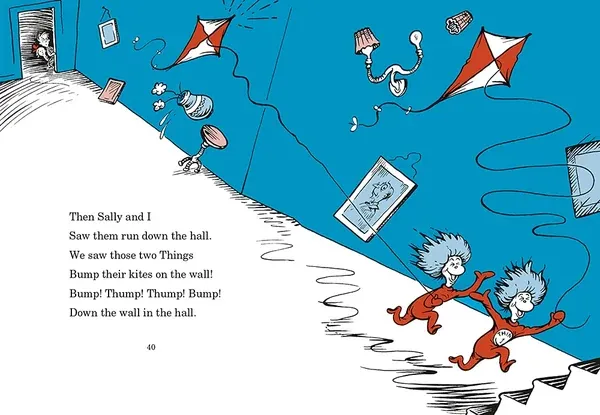

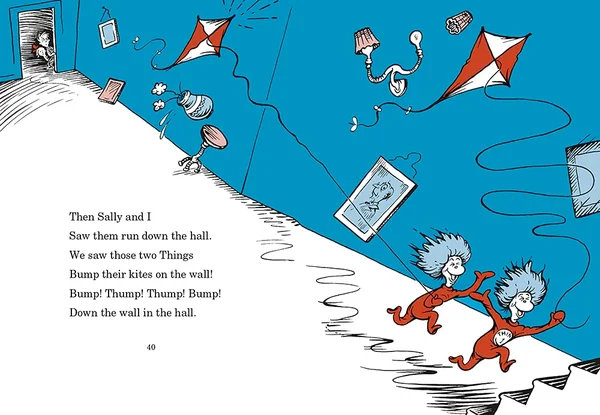

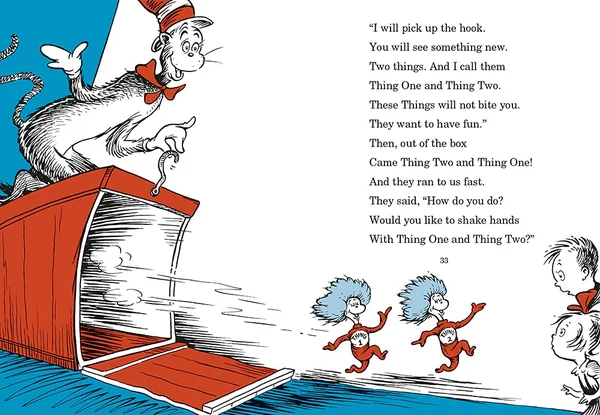

The story's climax introduces Thing One and Thing Two, the Cat's helpers who create magnificent mayhem throughout the house. As the mess reaches its peak, mother's impending return creates genuine tension. Will the children be caught? Will there be consequences?

The Cat's solution—a magical cleaning machine that restores perfect order—has sparked decades of debate among parents and educators. Some see it as teaching that rule-breaking has no real consequences. Others view it as fantasy fulfillment that allows children to explore transgression safely. The ambiguous ending, where Sally and her brother wonder whether to tell their mother about their visitor, leaves the moral question deliberately unresolved.

Where It Shows Its Age (and Where It Doesn't)

Nearly seventy years later, some elements feel dated. The assumption that children would be left unsupervised for extended periods, the gender dynamics of Sally staying home while her brother takes a more active role—these reflect 1950s domestic arrangements that don't match modern family life.

However, the core appeal remains timeless. Children still feel bored, still face rainy days, and still grapple with the tension between following rules and seeking excitement. The rhythm and repetition that made it revolutionary in 1957 continue to serve beginning readers perfectly. The illustrations, with their bold lines and limited color palette, feel fresh rather than old-fashioned.

The book's brevity—readable in one sitting—makes it ideal for children transitioning from picture books to early readers. Unlike some classic children's literature that requires adult mediation, The Cat in the Hat succeeds as independent reading material.

A Foundation Text Worth Keeping

The Cat in the Hat earned its status as a cornerstone of children's literature through practical innovation rather than literary pretension. Seuss solved the problem of boring early readers by proving that controlled vocabulary didn't require controlled imagination. The book's enduring popularity stems from its respect for children's intelligence and its willingness to address the moral complexities of growing up.

For parents wondering about appropriateness, consider your comfort level with stories that question authority. The Cat isn't dangerous, but he's definitely subversive. That subversion, wrapped in playful rhyme and bounded by fantasy, offers children a safe space to explore independence and consequence—themes that remain relevant regardless of the decade.

Where to Buy

You can find The Cat in the Hat at Amazon, your local bookstore, or directly from Random House Books for Young Readers.